I worked with an organization several years ago to develop a leadership coaching program. When I asked my client what the problem was, he said, “It is okay to be a jerk as long as you’re hitting your numbers.”

I worked with an organization several years ago to develop a leadership coaching program. When I asked my client what the problem was, he said, “It is okay to be a jerk as long as you’re hitting your numbers.”

The organization’s sales leaders were operating in an alienating manner, but this behavior was excused because they were meeting their goals. When those sales dipped, they didn’t have trusted confidants to point out industry and competitive shifts that led to the decrease.

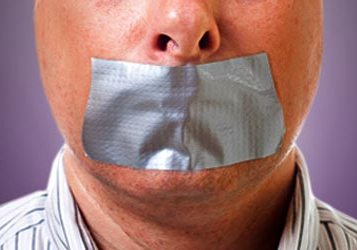

I liken this to the feedback some people receive regarding the things they say and the way they say them. It’s one thing to be right, and quite another to be rude about it. For a leader, being right is driving successful business results. Saying those things in the right way demonstrates the humility necessary to build relationships. Both factors must be present for individuals to attain leadership excellence.

Now consider NBA basketball star LeBron James. In the 2010 offseason, James signed as a free agent with the Miami Heat and faced a storm of criticism as the result. Why was he vilified when so many players in the sports world today opt to go the free agent route? It all goes back to what you say, and how you say it.

LeBron could have chosen a team to sign with and demonstrated professional courtesy to the other teams under consideration by informing them of this move in advance of holding a press conference. Instead, he strung teams along, including Cleveland, and announced his decision in a highly publicized and criticized ESPN live special entitled “The Decision.” LeBron and his Miami Heat teammates then hosted what appeared to be a post-championship celebration in their home arena before the season had even begun. Rather than a confident showman focused on the new goal ahead, many fans and media members saw arrogance and over-the-top flamboyance. The most notorious moment came when LeBron discussed his new team winning multiple championships as if it was a foregone conclusion.

LeBron was now firmly cast as a bad guy, yet even in this new role and on a new team he came up short yet again in the NBA championship series. The sports media criticized LeBron for not performing up to the level expected during crunch time moments of the 4th quarter. Unlike the last time he lost the big game, he was not given a pass.

This is the essence of leadership derailment. Derailing behaviors tend to emerge as coping mechanisms when we face stress or adversity. Over time these behaviors erode relationships. In the grand scheme of things, our positive achievements may outweigh our derailing moments in terms of sheer number. Regardless, the magnitude and weight of those derailing actions when we are at our worst tend to overshadow much of the good work we have done.

LeBron was likely coping with stress and adversity. He had always lived and played basketball in Ohio up to that point, and last season was clearly a time of stressful decisions and transitions. His charisma, showmanship, and confidence allowed him to harness his talents and become an MVP. These same characteristics became strengths overused and the negative moments are quickly becoming the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of LeBron. The 2012 season appeared to be the year of a humble King James until a recent altercation with a fan during a game has further perpetuated his bad guy image.

On my way to the airport this week, I heard a sports talk radio personality characterize LeBron as a good guy who tends to say or do things in big moments that rub people the wrong way or bring into question his ability to deliver in the clutch. These derailing moments will likely permeate his legacy and overshadow his multitude of great on-the-court achievements unless he is able to win multiple championships. Like those sales leaders I worked with years ago, it’s okay to be a jerk as long as you are hitting your numbers; however, true greatness is likely achieved through equal doses of driving results and demonstrating humility.

I’m a big movie buff. Since I have young children I rarely get a chance to go the movie theaters anymore to see a film that doesn’t star Woody, Buzz, Lightning McQueen, or a princess of some type. In my 5+ years of fatherhood, Netflix has become a savior in terms of feeding my movie addiction. For me and 20 million other subscribers, seeing that a new movie is available for streaming online or getting that red envelope in the mail is one of life’s simple joys.

I’m a big movie buff. Since I have young children I rarely get a chance to go the movie theaters anymore to see a film that doesn’t star Woody, Buzz, Lightning McQueen, or a princess of some type. In my 5+ years of fatherhood, Netflix has become a savior in terms of feeding my movie addiction. For me and 20 million other subscribers, seeing that a new movie is available for streaming online or getting that red envelope in the mail is one of life’s simple joys. An acquaintance of mine was recently sharing her on boarding experiences for a job she just started. She was hired her based on her experiences with dynamic talent management projects and they assigned her the mission of driving progressive change in the organization’s candidate selection and leadership development programs. An early indication of the obstacles standing in her way became clear when a colleague said, “Before we brainwash you into doing business as usual around here, tell me your ideas.” At least they were self-aware of their problem!

An acquaintance of mine was recently sharing her on boarding experiences for a job she just started. She was hired her based on her experiences with dynamic talent management projects and they assigned her the mission of driving progressive change in the organization’s candidate selection and leadership development programs. An early indication of the obstacles standing in her way became clear when a colleague said, “Before we brainwash you into doing business as usual around here, tell me your ideas.” At least they were self-aware of their problem!