The existing paradigm in the business world holds that successful CEOs are ambitious, result-oriented, individualistic, and, above all, charismatic. The rise of agency theory, or the notion that incentivizing managers should improve shareholder returns, put greater emphasis on the need to hire leaders that appear leader-like. Unfortunately, conventional wisdom of what a leader looks like is, quite simply, incorrect.

The existing paradigm in the business world holds that successful CEOs are ambitious, result-oriented, individualistic, and, above all, charismatic. The rise of agency theory, or the notion that incentivizing managers should improve shareholder returns, put greater emphasis on the need to hire leaders that appear leader-like. Unfortunately, conventional wisdom of what a leader looks like is, quite simply, incorrect.

Charisma is a very attractive characteristic in a leader. Yet, when promoted, these individuals create chaos and ruin for their organizations. Humility, rather, is a much better indicator of leadership success. Jim Collins, renowned author of Good to Great, conducted extensive research on organizational success. His work clearly demonstrated that companies led by modest managers consistently outperformed their competitors, and tended to be the dominant players in their sectors. Moreover, humble leaders tend to stay at their organizations longer than their arrogant counterparts, and their companies continue to perform well even after they leave because humble leaders often ensure a succession plan before they depart.

The Problem with Charisma

Organizations tend to be good at identifying people who “look” like leaders. Individuals who seem confident, bright, charismatic, interesting, and politically savvy tend to get earmarked for promotion. Personality assessments show that charismatic leaders rank highly on measurements of self-confidence (Bold), dramatic flair (Colorful), readiness to test the limits (Mischievous), and expansive visionary thinking (Imaginative). These leaders know what it takes to get ahead and get noticed, and they strategically cater to individuals and audiences who can offer them power, influence, status, or access to resources. While these individuals are highly interpersonally savvy and excellent self-promoters, they lack basic leadership and management skills.

Although some charisma can be beneficial, it often leads to lower levels of leadership effectiveness. One possible explanation is that highly charismatic leaders may be more strategically ambitious but less effective at the day-to-day operations. Emergent (read: charismatic) leaders, or individuals who stand out from the crowd, get promoted because they spend their time politicking and networking – trying to please their bosses by managing up rather than being concerned with those working under them.

Emergent leaders also create a culture of competition, ambition, and narcissism. Leaders like people like themselves, so senior leaders are more likely to choose successors who best reflect the status quo. Of course, competition and ambition can be positive qualities in the business world, but not if it comes at the expense of actual hard work.

Humility Breeds Effectiveness

Whereas charismatic leaders tend to focus on personal advancement, humble leaders tend to focus on team performance and guiding their employees. Effective leaders are more modest; they are willing to admit mistakes, share credit, and learn from others. Higher levels of humility also lead to higher rates of employee engagement, more job satisfaction, and lower rates of turnover. To be clear, humility does not imply the absence of ego or ambition. Rather, humble leaders are better able to channel their ambition back into the organization, rather than use it for personal gain.

Humility is broadly defined as 1) self-awareness, 2) appreciating others’ strengths and contribution, and 3) openness to new ideas and feedback regarding one’s performance. Leaders who are humble have a better grasp on organizational needs and make better informed decisions about task performance. They are also better able to ask for help than their charismatic counterparts. What’s more is that humble leaders help to foster a culture of development with their employees by legitimizing learning and personal development. Humility also encourages cultures of openness, trust, and recognition, which are important precursors to success.

Dig Deeper to Identify Humble Leaders

The challenge in hiring and developing strong leaders is in their identification. Charismatic, or highly emergent, leaders easily stand out from the crowd and their likability masks more important characteristics of performance. Humble, and typically more effective, leaders may fly under the radar and be passed over for hiring or promoting. Building selection and development programs that overcome personal biases and focus on objective indicators of success can help identify these low flyers. Organizations can benefit from the use of psychometric testing and 360 evaluation to counteract political factors by developing a data-driven approach that ensures organizations recognize and promote those who will be effective and humble leaders.

This article was originally published in Talent Economy.

Hogan is proud to officially announce the addition of

Hogan is proud to officially announce the addition of  *This interview was originally published in Business Class Magazin – this is the translation of the Hungarian text. The original version can be found

*This interview was originally published in Business Class Magazin – this is the translation of the Hungarian text. The original version can be found  *This article was written by Danielle King and

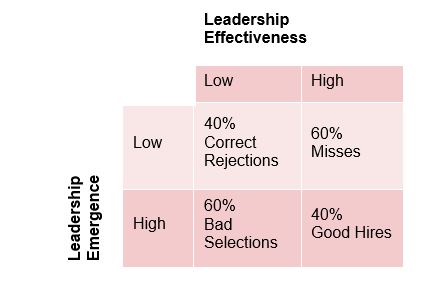

*This article was written by Danielle King and  THUOPER, Hogan’s Colombian distributor, embodies one of Hogan’s core values: developing future leaders. Ineffective leadership has plagued the global workforce for centuries, mostly because the characteristics that help people emerge as leaders are quite different from those that make an effective leader.

THUOPER, Hogan’s Colombian distributor, embodies one of Hogan’s core values: developing future leaders. Ineffective leadership has plagued the global workforce for centuries, mostly because the characteristics that help people emerge as leaders are quite different from those that make an effective leader. The situation in Colombia is no different. Moreover, the lack of coordination and coherence between the academic world and the organizational world is worsening. Responding to this situation, THUOPER decided to take action on the matter. Since 2016 we have teamed up with CESA (College of Advanced Studies in Administration), a private university located in Bogotá that specializes in Business Administration, to create the CEOPPORTUNITY program.

The situation in Colombia is no different. Moreover, the lack of coordination and coherence between the academic world and the organizational world is worsening. Responding to this situation, THUOPER decided to take action on the matter. Since 2016 we have teamed up with CESA (College of Advanced Studies in Administration), a private university located in Bogotá that specializes in Business Administration, to create the CEOPPORTUNITY program. *This article was authored by Robert Hogan and Joan Jacobsen, and

*This article was authored by Robert Hogan and Joan Jacobsen, and  *This post was authored by Robert Hogan & Ryne Sherman.

*This post was authored by Robert Hogan & Ryne Sherman. *This is a guest post authored by Dr. Nicholas Emler, Professor of Psychology at University of Surrey.

*This is a guest post authored by Dr. Nicholas Emler, Professor of Psychology at University of Surrey. *This Q&A was

*This Q&A was