Bad followership can destroy team performance. Followership concerns the level of engagement and critical thinking skills demonstrated by team and group members. A group member may have all the right skills and be in the right role, yet sit in the corner and pout rather than perform. Other members may have fewer skills but work hard and offer good ideas for improving processes which, ultimately, improves team functioning.

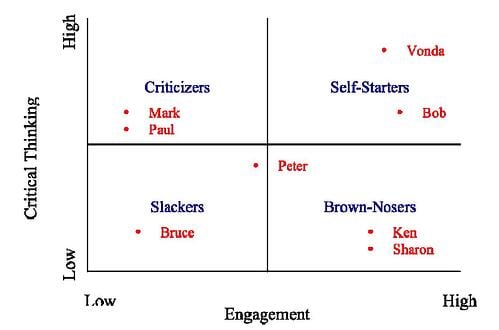

As seen in the diagram, engagement and critical thinking are independent dimensions of followership. These two dimensions can be divided into four followership types: Self-Starters, Brown-Nosers, Slackers, and Criticizers. The power of the model becomes obvious when leaders use it to assess the follower types on their team or group. Knowing members’ types will provide leaders with insights on how best to manage them since each type should be approached differently. .

Self-Starters, such as Bob and Vonda, are individuals who are passionate about working on the team and will try to make it successful. They constantly think of ways to improve team performance by raising issues, developing solutions, and showing enthusiasm. When they encounter problems, they resolve issues and then tell their leaders what they have done rather than waiting to be told what to do. This follower type will improve their leaders’ performance by offering opinions before, and providing constructive feedback after, bad decisions. Self-Starters are critical to the performance of teams and are the most effective follower type.

Brown-Nosers such as Ken and Sharon have a strong work ethic but lack critical thinking skills. Brown-Nosers are dutiful and conscientious, rarely point out problems, raise objections, or make waves, and do whatever they can to please their boss. Brown-Nosers constantly check with their leaders and operate by seeking permission rather than forgiveness. Leaders who feel entitled, think they are hot, or think they are the only ones capable of developing solutions, often surround themselves with Brown-Nosers because suck-ups constantly flatter their great bosses. Brown-Nosers often go far in organizations, particularly in those that lack objective performance metrics. Organizations lacking clear measures of performance often make personnel decisions based on politics, and Brown-Nosers play politics very well.

Slackers don’t work very hard, think they deserve a paycheck for just showing up, and believe it is the leader’s job to solve problems. Slackers are clever at avoiding work, often disappear for hours, look busy but get little done, have good excuses for not completing projects, and spend more effort finding ways to avoid finishing tasks than they would by just doing them. Slackers are “stealth employees” who are happy to spend their time surfing the Internet, shopping online, gossiping with co-workers, and taking breaks with no concern for their jobs.

Criticizers are followers with strong thinking skills who are disengaged. Rather than directing their analytical skills to productive outcomes, they find fault in anything their leaders and organizations do. Criticizers educate co-workers about their leaders’ shortcomings, how change efforts will fail, how poorly their organizations compare to the competition, and how management ignores their suggestions. In terms of their impact on team and organizational performance, they are the most dangerous of the four types because their personal mission is to create dissent. If not managed properly, these team killers can take over teams and entire departments!

Leaders can use the followership model to understand group dynamics and what they need to do to improve team talent within any team or group. These four follower types are dynamic—they can and do change over time. Members who were once Self-Starters can become Criticizers and vice-versa. Because follower types are dynamic, leaders should periodically assess their own behavior and use the followership model to evaluate the impact it is having on the people in their groups.

By Gordon Curphy

Curphy Consulting Corporation

Guest blogger and co-author of The Rocket Model

Strong leadership is a crucial ingredient for a successful company. With highly qualified people at the top, the entire organization is more likely to outperform the competition and hold on to their most talented employees. Yet, many organizations lack a tried-and-true method for identifying and developing those employees who show leadership potential.

Strong leadership is a crucial ingredient for a successful company. With highly qualified people at the top, the entire organization is more likely to outperform the competition and hold on to their most talented employees. Yet, many organizations lack a tried-and-true method for identifying and developing those employees who show leadership potential. Evidence shows that at least 50% of individuals in leadership have, will, or are failing. The vast majority of suggested solutions revolve around high potential identification, leadership development programs and the like. The purpose of such initiatives is to identify the individuals who should be leaders, but given the statistic above, one has to wonder about their effectiveness.

Evidence shows that at least 50% of individuals in leadership have, will, or are failing. The vast majority of suggested solutions revolve around high potential identification, leadership development programs and the like. The purpose of such initiatives is to identify the individuals who should be leaders, but given the statistic above, one has to wonder about their effectiveness.