Topics: leadership, judgment, integrity, trust

An individual’s ability to exercise leadership is hinged on his or her ability to persuade others to follow. According to the Hogan Leadership Model, followers look for four essential qualities in a leader: integrity, judgment, competence, and vision. Of these, integrity is most essential.

An individual’s ability to exercise leadership is hinged on his or her ability to persuade others to follow. According to the Hogan Leadership Model, followers look for four essential qualities in a leader: integrity, judgment, competence, and vision. Of these, integrity is most essential.

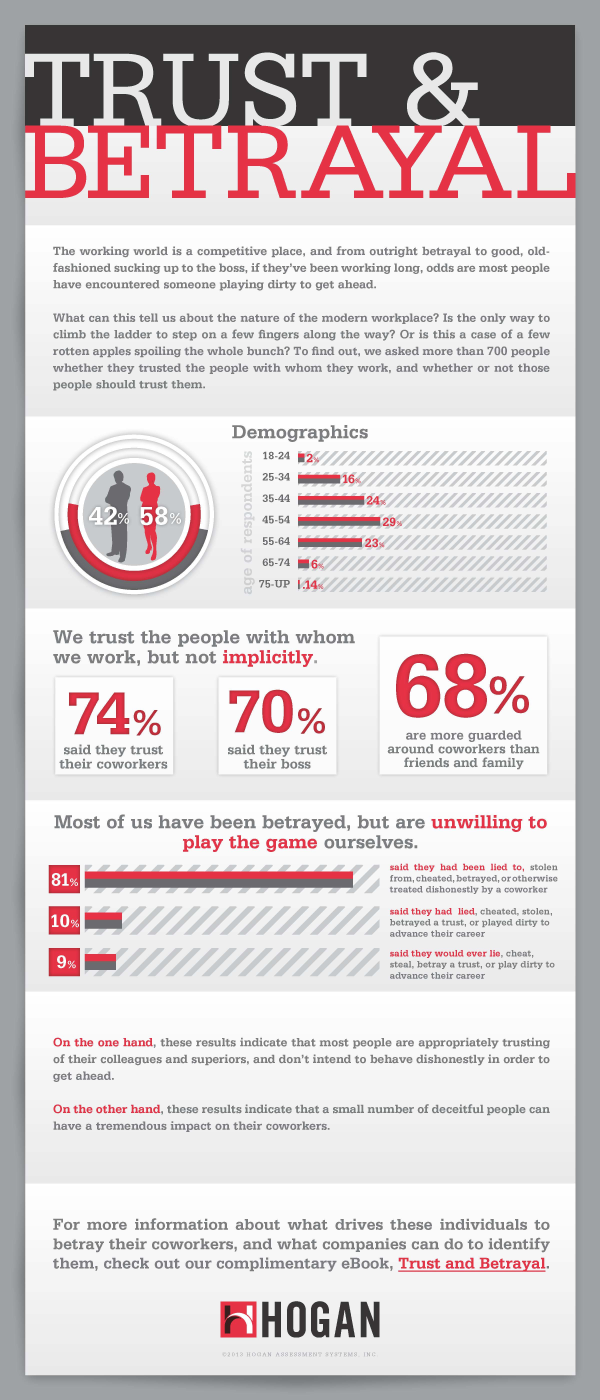

In a recent survey, Hogan asked more than 1,000 individuals about the qualities of their all-time best boss. Eighty-one percent of respondents said trustworthiness was their most important personality characteristic. Conversely, 50% described their worst boss as deceitful.

“People need to know that the person in charge won’t take advantage of his or her position,” said Dr. Robert Hogan, founder of Hogan Assessments. “That they won’t lie, steal, play favorites, and betray subordinates.”

In a separate study, Dr. Hogan and Hogan co-founder and former vice president Dr. Joyce Hogan gathered personality data and performance ratings from the immediate supervisor and subordinates of 55 managers at a large transportation company. Statistical analysis revealed that subordinates ratings of their managers’ overall effectiveness was directly tied to the degree to which a manager was trusted.

Unfortunately, as the as the past decade of scandal, corruption, and Congressional hearings proved, there are an alarming number of dishonest people in leadership roles. Our latest complimentary eBook, Trust and Betrayal, examines who these people are, and how companies can prevent them from damaging their workforce.

Topics: leadership, judgment, integrity, trust

In their book chapter “The Mask of Integrity,” published in Citizen Espionage: Studies in Trust and Betrayal, Drs. Joyce and Robert Hogan, outlined four characteristics that typified the ideal betrayer:

In their book chapter “The Mask of Integrity,” published in Citizen Espionage: Studies in Trust and Betrayal, Drs. Joyce and Robert Hogan, outlined four characteristics that typified the ideal betrayer:

Charisma – According to Dr. Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, vice president of research and innovation at Hogan, there are three ways to influence others: force, reason, or charm. Force and reason are rational – even when people are forced to do something, they obey for a good reason. Charm, on the other hand, is based on emotional manipulation and has the ability to trump rational assessments.

Self-absorption – The second characteristic of an ideal betrayer is an unusual degree of self-absorption, or, more to the point, a relentless drive for self-advancement. Betrayers possess a ruthless dedication to self-advancement to the extent that other people lose their value as humans and become objects to be manipulated.

Self-Deception – The third characteristic that typifies the ideal betrayer is self-deception. A major tenet of psychoanalysis and existentialism is that people are prone to deceive themselves about the reasons for their actions.

Hollow Core Syndrome – The final characteristic of the ideal betrayer is a pattern of personality characteristics called the hollow core syndrome. The hollow core syndrome refers to people who are overtly self-confident, who meet the public well, who are charming and socially poised, and who expect others to like them, but who are privately self-doubting and unhappy.

Unfortunately, this charm, confidence, and talent for ingratiation provides betrayers the tools they need to find employment at and quickly ascend the ranks of large, hierarchical organizations, and the private self-doubt associated with the hollow core fuels their pursuit of the money, power, and prestige offered by senior management positions. Trust and Betrayal, a new eBook from Hogan, examines what companies can do to identify and mitigate the effects of betrayers in their ranks.

Topics: leadership, judgment, integrity, trust

Recent events in politics and business again show the importance of personal integrity in everyday affairs, especially at the leadership level. Our analysis of the psychology of integrity suggests that the topic, although a crucial element in human affairs, is somewhat more paradoxical than it might appear at first blush.

Recent events in politics and business again show the importance of personal integrity in everyday affairs, especially at the leadership level. Our analysis of the psychology of integrity suggests that the topic, although a crucial element in human affairs, is somewhat more paradoxical than it might appear at first blush.

In Memories, Dreams, and Reflections, Carl Jung describes meeting Albert Schweizer (1875-1965), the legendary theologian, organist, philosopher, and physician known for founding a hospital for the poor in Gabon. Schweizer received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952, and by anyone’s standards qualifies as a great moral figure. Jung reported that he spent two days prying at Schweizer, trying to find the neurotic underpinnings for his moral nobility, and he could find nothing. Then Jung noted that he met Schweizer’s wife, and Schweizer’s narcissism was revealed. Similarly, Erik Erikson wrote a psycho-biographical study of Mohandas Ghandi, the “great-souled father” of modern India, the man who invented non-violent civil disobedience as a way of protesting political oppression, and virtually everyone’s prototype of a great moral figure. Erikson was so disgusted by Gandhi’s hypocrisy and narcissism that he almost abandoned the project. Mother Theresa similarly fails to hold up well under close moral scrutiny.

When we say a person behaves with integrity, we are commenting on how that person behaves vis-a-vis the rules of the game he/she is engaged in. The manner in which people accommodate themselves to the rules of games passes through three developmental stages, as noted for example by Jean Piaget in The Moral Judgment of the Child, a book based in large part on his observations of children playing marbles. In the first stage, children must learn that to take part in the game, they must follow the rules of the game—and if they don’t, the game falls apart. One sign of a delinquent is a pronounced tendency to break normal rules of conduct; one sign of integrity is the tendency to follow rules scrupulously.

Godel’s theorem holds that in any relatively complex system of rules, conflicts inevitably emerge. Godel was thinking of mathematics, but his observation holds for human rule systems as well. In any game, at some point, following the rules will lead to bad results. The second developmental stage concerns understanding the “spirit of the game,” developing a sense of “sportsmanship” or fair play which allows people to set rules aside temporarily in order to allow justice to prevail. Piaget says this sense of sportsmanship comes from the process of learning to “take turns” which leads to the concept of reciprocity and then justice. In any case, we often say a person has integrity when he or she displays outstanding sportsmanship and acts not according to self-interest but according to the spirit of the game.

The third developmental stage is more abstract, and concerns becoming an advocate for the game, an ambassador for cricket or football or tennis—or Catholicism, Islam, capitalism, or any other belief system. We often say a person has integrity depending on how well he/she performs in this role.

These three stages in the development of performances that lead to the attribution of integrity are associated with individual differences in overt behavior, which is why we can make the attributions of integrity. One class of behavior refers to good citizenship and being a good role model by strictly observing rules. People with high scores, for example, on the Socialization scale of the California Psychological Inventory are utterly dependable and respect the rules; there is always a dark side associated with over- or under-doing the rule following. The under-doers are flexible, spontaneous, and not always dependable; the over-doers are often rigid, judgmental, and inflexible.

The second stage concerns a continuum that ranges from egocentrism and self-centered behavior at the low end to socio-centrism and a lack of resolve at the high end. This can be measured, for example, with the Empathy scale of the California Psychological Inventory. The third stage concerns a continuum that ranges from pragmatism at the low end to ideological fervor at the high end.

To summarize, integrity exists in the eyes of the beholder, not in the psyches of the actors; integrity refers to evaluations that we put on other peoples’ performance. More specifically, integrity refers to evaluations in three areas of performance—rule following, sportsmanship, and advocacy. In addition, we can assess peoples’ typical performance in these three areas, and data associated with those assessments leads to two major conclusions. First, generally speaking, integrity is a good thing. Second, there is a definite dark side to integrity, as exemplified by the lives of such great moral figures as Albert Schweizer, Mohandas Gandhi, and Mother Teresa.

Topics: leadership, integrity, character